Stanley Diamond’s “Primitive Ritual Drama”

[1] (abridged paraphrase)

According to Stanley Diamond, primitive ritual drama comprises ceremonies clustering around the life crises and discontinuities of individuals and communal groups. Diamond refers to these ceremonials as “dramas” because of their dominant emphasis upon the themes of identity and survival. The crises and discontinuities represented within these primitive ritual dramas concern both the individual’s relation to himself and the group, and the group’s relation to the natural environment—with an apparent continuity between the individual’s setting in the group and the group’s setting in nature. In the ritual drama, art and life converge; life itself is seen as a drama, roles are symbolically acted out, dangers confronted and overcome, and anxieties faced and resolved. Relations among the individual, society, and nature are defined, renewed, and reinterpreted.

Ritual drama focuses on ordinary human events and makes them extraordinary and, in a sense, sacramental. In primitive societies, ordinary human events or existential situations—such as death, marriage, puberty or illness—are made meaningful and valuable through the medium of dramatic ceremonies. The ceremonies of primitive ritual drama served to affirm human identity and define the individual’s obligations to himself and the group. Such ceremonies also enabled the individual to maintain integrity of self while changing life roles.

The ceremonies of primitive ritual drama free the person to act in new ways without either suffering crippling anxiety or becoming a social automaton. As illustrated by the theme of death and rebirth frequently encountered in primitive ceremonials, the person transitioning between roles undergoes psychic renewal: this person discharges the new status but the status does not become the person. The ceremonies represent and celebrate such transitions as gradual, realistic processes. What one is, emerges organically out of what one was, with no mechanical separation.

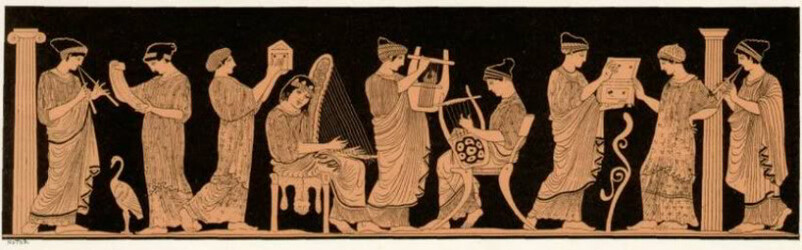

Ceremonial dramas constitute a shaping and acting out of the raw materials of life. Ceremonies of personal crisis affirm the human struggle for values within a social setting, while confirming individual identity in the face of ordinary “existential” situations such as death or puberty. All “primitives” have their brilliant moments on this stage, each becomes the focus of attention by the mere fact of his humanity; and in the light of the ordinary-extraordinary events, his kinship to others is clarified. Such ritual dramas, based on the typical crisis situations, seem to represent the culmination of all primitive art forms. They are, perhaps, the primary form of art around which cluster most of the aesthetic artifacts of primitive society—the masks, poems, songs, myths, and above all the dance.

Ritual dramas—like the poems, dances and songs that heighten their impact—were created by individuals moving in a specific cultural sequence. These individuals are both formed by their tradition and engaged in forming it. These primitive dramatists, whom Paul Radin calls “poet-thinkers,” “medicine men” and “shamans,” were individuals who reacted with unusual sensitivity to the stresses of the life cycle. In extreme cases, they were faced with the alternative of breaking down or creating meaning out of apparent chaos. The meanings they created, the conflicts they symbolized and sometimes resolved in their own “pantomimic” performances, were felt by the majority of so-called ordinary individuals with whom they shared a common perception of human nature. The primitive dramatist served as the lightning rod for the commonly experienced anxieties, which, in concert with his peers and buttressed by tradition, the primitive individual was able to resolve. The primitive dramatist shaped dramatic forms through which the participants were able to clarify their own conflicts and more readily establish their own identities.

The primitive dramatist and the people at large were bound by the organic tie of creation and response. While popular response is itself a type of creation, the dramatist lived under relatively continuous stress, most people only periodically so. Thus the dramatist was in constant danger of breakdown, of ceasing to function or of functioning fantastically in ways that were too private to elicit a popular response.[2] The very presence of the shaman-dramatist—the implicit necessity of his social function—is a reminder that life often balances on the knife edge between chaos and meaning and that meaning is created or apprehended by the human-being coming, as it were, naked into the world.

[1] For Stanley Diamond the “search for the primitive” is the search for a primary or essential human nature.

[2] In this prototypical primitive situation, we can, I think, sense the connection that binds the psychotic to the shaman whom we have called a dramatist and the dramatist to the people at large.